This website is an interactive scholarly work that uncovers the history of the Bible in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century United States. Using computational methods, this project has found biblical quotations in two large corpora of historical American newspapers. By identifying, visualizing, and studying quotations in American newspapers, the site offers a commentary on how the Bible was used in public life over one century of American history.

Here are some suggestions about how to get started, or you can begin with the table of contents below.

How to use this website

This website contains elements akin to a traditionally published book, but it also contains interactive elements that take advantage of the medium of the web. All of the elements of this website are accessible from the home page, which serves as a table of contents.

The different elements of the site form an interpretative pyramid, something like the e-books that Robert Darnton envisioned:

- At the base are quotations in the newspaper. You can browse the gallery of quotations to see examples or see the datasets for a complete list.

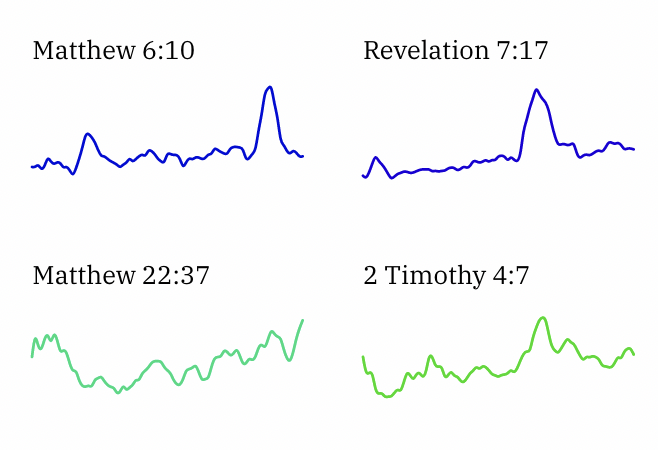

- Those quotations are aggregated into trend lines, which are accompanied by tables of quotations. You can start by browsing the featured verses.

- Verse histories take the information from the trend lines and the quotations and offer brief interpretative essays on their history.

- Longer essays introduce the site and its methods and address other questions on the history of the Bible in the United States.

Essays and explorations

Preface

An overview of this interactive scholarly work.

Introduction: Commenting on America’s public Bible

What does it mean to study America’s public Bible in historical newspapers?

Methods: The how and the why of finding biblical quotations

How this site uses the methods of machine learning, but also an approach to interpretation called disciplined serendipity.

Bible-filled pages: Newspaper pages that were primarily Bible quotations

Which newspaper pages were covered in Bible verses and why?

Steadily quoted: The most quoted verses

Which verses were the most quoted across the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

Bibliography

“Render therefore to all their due: … honor to whom honor.”

Verse histories

Law and order

Romans 13:1—“Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers ...”

A leading text for those who advocated for law and order, from the Fugitive Slave Act to immigration laws.

Good advice, ancient and modern

Proverbs 15:1—“A soft answer turneth away wrath: but grievous words stir up anger.”

Newspapers were full of advice literature, and where better to learn how to govern the tongue than the Proverbs?

Losing the soul to greed by Caitlin McGeever

Matthew 16:26—“For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

A text at the intersection of American capitalism and American Christianity.

Submission and authority

Ephesians 5:22—“Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands.”

A text on the relationships between husbands and wives had broader connections to slavery and political authority.

Prove all things

1 Thessalonians 5:21—“Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.”

A proverbial verse which could fit nearly any context.

Trends in biblical quotations

The heart of this site is a set of interactive visualizations that let you see the trend in the rate of quotations for any given verse in Chronicling America and Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, then see examples of those quotations on the newspaper page at Chronicling America.

If you have a verse you want to look up directly, you can search for it below. (Note that the lists of verses are rather selective and so return verses with higher quality results. The verse search feature below returns many more verses, and the quality of the results for some verses may therefore be lower.) You can search for either the reference of the verse (e.g., “Genesis 1:1”) or the text of the verse in the King James Version (e.g., “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth”).

Below are the trends for featured verses, a few of which are also the subject of the verse histories. You can also browse the verses in three other ways: (1) the most quoted verses in descending order of frequency; (2) verses that had a peak rate of quotation in a given year, arranged chronologically; and (3) frequently quoted verses in their order in the Christian Bible.

Verses most quoted Verses chronologically Verses in biblical orderFeatured verses

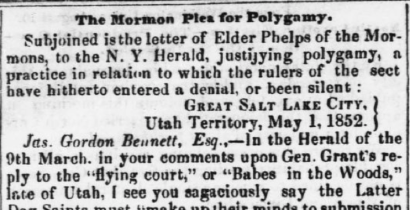

Quotations gallery

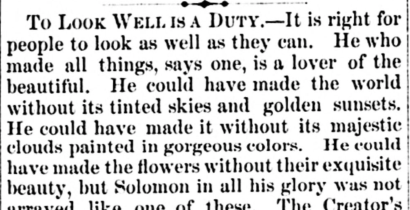

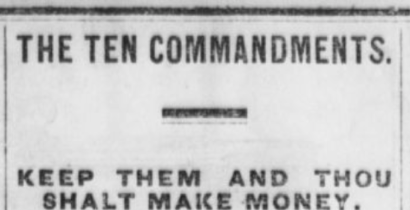

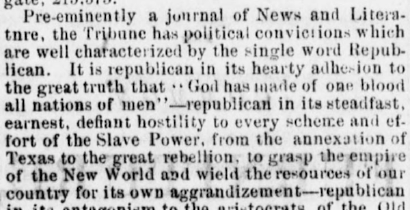

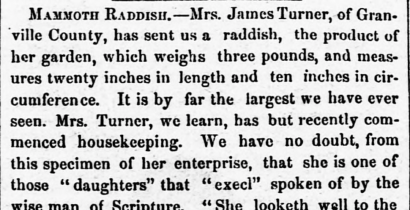

Striking examples of quotations from the Bible in newspapers.

Appendix: Data and code

Data

Data that was generated for this project is available for your use.

- apb-quotations.csv.gz (16.7 MB gzipped): the quotations found for this version of the website.

- apb-quotations-prototype.csv.gz (46.9 MB gzipped): the quotations found for the earlier prototype version of the website.

- apb-matches-for-model-training.csv.gz (252 KB gzipped): the labeled data used for training the model.

Code

All of the code for this project is available on GitHub. This includes the code that created the prediction model for identifying quotations; data analysis notebooks; and the source code for this website and its visualizations. Part of this website is served via a data API hosted by RRCHNM.

Computing Cultural Heritage in the Cloud

Working in collaboration with the LC Labs in fall 2021, I extended this project beyond Chronicling America to other Library of Congress digital collections. You can find more about the Computing Cultural Heritage in the Cloud project at the LC Labs website. You can find my work for that project on GitHub.

Suggested citation

If you use this project, you can cite it using this suggested format.

Lincoln A. Mullen, America’s Public Bible: A Commentary (Stanford University Press, 2023): https://americaspublicbible.org, https://doi.org/10.21627/2022apb.

About the author

This project was created by Lincoln Mullen, a historian of American religion at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. Mullen is the author of The Chance of Salvation: A History of Conversion in America (Harvard University Press, 2017), which won a prize for Best First Book in the History of Religions from the American Academy of Religion. In 2016, a prototype version of America’s Public Bible won the Chronicling America Data Challenge from the National Endowment for the Humanities. At RRCHNM, Mullen has led projects including American Religious Ecologies, Legal Modernism, and Models of Argument-Driven Digital History.

For updates about this project and about other work at the intersection of the history of American religion and digital history, you can subscribe to either his personal newsletter, “Working on It,” or to the “American Religion @ RRCHNM” newsletter.

About RRCHNM

This work of scholarship was created at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media.

At the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, we use digital media and computer technology to democratize history: to incorporate multiple voices, reach diverse audiences, and encourage popular participation in presenting and preserving the past. Since 1994, RRCHNM has worked to create digital history and software that is free and fully available to all.

Acknowledgements

Within the collaborative realm of digital history, this project is about as close as you can get to a single-author work. Nevertheless, the long list of people who have contributed to it shows how reliant I have been on colleagues, friends, and the infrastructure of libraries and research universities.

In the first instance, the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress created the Chronicling America Data Challenge, which provided the impetus for creating this project. Thanks to Leah Weinryb-Grohsgal for creating the competition, and thanks to the NEH for inviting me to speak to the National Digital Newspaper Program’s annual meeting in 2016 about this project. Over and above the amazing collection they have created, the Chronicling America team at the Library of Congress has been very generous in guiding my access to their corpus. Nathan Yarasavage in particular answered many questions and arranged special access for downloading the bulk data. At George Mason University, George Oberle arranged for rights to the bulk data for Gale’s Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, which are used by permission, and he has always generously supported my research as both a librarian and a colleague.

Much of the computation for this project happened on a virtual cluster provided by the Office of Research Computing at George Mason University. In particular, Jayshree Sarma and Dmitri Cherbotarov provided invaluable assistance and access to computing resources. (This project was supported by resources provided by the Office of Research Computing at George Mason University and funded in part by grants from the National Science Foundation [awards number 1625039 and 2018631].) Tyrus Berry discussed machine-learning methods with me, helping me gain confidence that my idea for finding quotations could work. Jenny Bryan pointed me to statistical tests for runs. Much later, the Library of Congress Labs invited me to be a researcher on their Computing Cultural Heritage in the Cloud project, building on my work on this project. Thanks to Olivia Dorsey, Meghan Ferriter, Alice Goldfarb, and Jaime Mears for making that time possible. While no historical research is possible without libraries and archives, computational historical research like this is especially indebted to the infrastructure of library and archives made freely available as a public good.

At Stanford University Press, Friederike Sundaraam was more patient than I could possibly have hoped about the length of time it took to complete this project. I am grateful for the her faith in the project and the willingness of the press to wait for it during the time it took me to get it right, even as they faced their own pressures to get a digital publishing program off the ground. I appreciate the genuinely useful comments from the anonymous peer reviewers provided during both rounds of peer review. Thanks to Jasmine Mulliken for seeing the project through the production process, and to Amanda DeBord for copyediting.

While this project was in development, many scholars at other institutions were kind enough to offer their expertise and often to invite me to speak about the project. Mark Noll’s 2016 conference paper, “Presidential Death and the Bible: 1799, 1865, 1881,” at the American Society of Church History, served as the inspiration for this project. Mark was kind enough to then invite me to be a panelist for “The Bible in American History” at the John W. Kluge Center of the Library of Congress. Louis Epstein at St. Olaf’s College, Lauren Tilton and Taylor Arnold at the University of Richmond, and Mickey Casad at Vanderbilt University’s Center for Digital Humanities invited me to give talks or join colloquia at their institutions, while Chad Gaffield and Ian Milligan invited me to a workshop on “Quantitative Analysis and the Digital Turn in Historical Studies” at the Fields Institute for Mathematical Studies. At Vanderbilt, Jimmy Byrd has been a generous supporter of the project, and a key user of it for his excellent book, A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood. Likewise Chris Gehrz has made frequent use of the project to write insightful verse histories for his blog posts at The Anxious Bench, which were encouraging to me as a sign that other people found value in using the project for their research.

As an institution, the demands of collaborative research and administration at RRCHNM frequently competed against spending time on this project, but as a group of people, my colleagues at RRCHNM were always supportive of my working on the project, including Mills Kelly, Jessica Otis, Amanda Madden, and Jason Heppler. I am grateful for the comments of RRCHNM’s data working group in particular. Bridget Bukovich graciously agreed to help with the publicization of the project.

I am sure there is no more congenial place to do digital history research than the Department of History and Art History at George Mason University. My colleagues, including two excellent chairs, Brian Platt and Matt Karush, never once batted an eye about this weird, strange project being scholarship. On the contrary, my colleagues were universally supportive of the project. Stephen Robertson in particular has been a wonderful conversation partner about the form of digital scholarship. John Turner is my collaborator on all things American religion, and a truly generous, supportive friend. Kellen Funk at Columbia Law School is my collaborator in all things related to text analysis and history, even if he would have preferred I spend more time on legal history with him.

I am grateful for the research assistance of Liv Vermane in summer 2020 and Caitie McGeever in summer 2021. Caitie in particular created many of the items in the quotation gallery and wrote her own verse history. All of Caitie’s and Liv’s written contributions appear under their byline on this site. A leave from my department in spring 2022 enabled me to finish this project.

Thanks to Abby, Maggie, and Paul for their love. This project owes its origin to my dad. One day when I was a teenager he brought The Age of Federalism and Sams Teach Yourself Java in 21 Days home from the bookstore, supporting all of my interests no matter how disparate or disant from his own. I doubt that this project is what he was expecting would result some two decades later, but whatever I have done in life is because of the love and support my parents gave me.